The Green Man as a Portal

The Green Man, or Jack in the Green, has long symbolised renewal, nature’s resilience, and the cycles of life. Emerging in folklore as a liminal figure between wilderness and civilisation, he embodies survival outside the bounds of settled society.

For people experiencing homelessness today, his image resonates as a guardian of those living in public, untamed spaces, hidden in plain sight, weathering the seasons, and forging an existence between visibility and invisibility. In this way, the Green Man becomes a contemporary emblem of endurance, dignity, and the fragile, enduring connection between human life and the natural world.

The Green Man as a Portal, By Amanda Camenisch

He is there. His presence felt. In the dim hush of a sacred space we can feel his eyes, carved yet alive, staring with the knowing of forgotten pasts. A teaching without words, older than memory, whispering that we are all the same. All drawn from the same material. All destined to return to the same dark humus of the earth. A vast cycle stretches out, beyond reach, cold and ungraspable, yet it coils within the body, pulsing through every vein.

The figure of the Green Man has long stood as a liminal emblem of renewal, resilience, and the eternal cycles of life. Carved into medieval churches, hidden in temples, whispered through folklore, he emerges at the threshold between wilderness and civilisation: both guardian and reminder of our entanglement with nature.

To think such thoughts is one thing, to feel them another. The mind can name unity, eternity, rebirth. The body trembles. The body resists. For in sensing the vastness, something ancient awakens: that raw, unreasoning part where survival is all that matters. A hunger that does not bow to language, a will that knows no law. It whispers of endings, of decay, of the fragility of breath.

The Green Man draws this contradiction into form. He is not only benevolent, not only savage. He smiles with leaves spilling from his mouth, yet his laughter tastes of rot. He thrives in the blossom that will soon collapse into mulch. His foliage mouths open in silence yet declare the oldest truth: that creation devours itself, that decay feeds life, that every beginning is already a return.

Perhaps this is why he appears on stones where prayers were once offered. Not as ornament, but as reminder. That beneath every sermon, beneath every empire, beneath even mercy itself, there runs a law without pity. Nature is not Eden. It does not distinguish between what is good and what is evil. It grows, it consumes, it transforms. To enter into its rhythm is not to discover moral clarity but to dissolve in an endless round of vanishing and renewal.

And yet, humans are not merely swallowed. We carve ourselves from nature even as we remain bound to it. It is not out of hunger that we fashioned ritual but out of remembrance of the divine. It is not out of fear we forged culture, but out of a desire to live in harmony. The rules we shaped were not to imitate nature but to soften its severity. Mercy does not spring from the soil; nor is it our own fragile creation. Without it we collapse back into the jungle of tooth and claw, into the impulse that cannot see beyond itself.

The Green Man lingers at the threshold, reminding us that the wild is always close, that culture without compassion withers, that roots without balance strangle. He shows us what we refuse: that in the pursuit of purity we generate shadow, in the pursuit of endless ascent we sever what sustains us. Every empire that sought only the good, only the true, only the perfect, fell beneath the weight of what it cast aside.

His lesson is quiet but relentless. Do not forget what you are made of. Do not imagine yourself free of soil and decay. Do not dream of rising to the heavens without knowing the roots that hold you to the ground. For those who deny this balance, shadow grows vast, and what is repressed returns in forms too dark to master.

Society makes a promise it struggles to keep. A vision of individuals gathered together, bound by laws meant to guard the wellbeing of all. Shining futures, perfected health, endless opportunity. Yet what does not fit this dream is cast aside. What is fragile, wounded, or in need of care becomes a burden, a hindrance, an unwanted remainder. The dirt no one wishes to see, the labour no one wishes to do. But this labour is not only external. It is within us, the work of tending the wildness we all carry.

Here, in our own time, the Green Man’s presence gathers force. He reminds us that harmony cannot mean denial. That to live well is not to sever wildness but to live with it, to balance the raw and the tender.

In the streets where people sleep on cold stone, in the doorways where bodies endure the seasons without walls, he lingers. Homelessness is not personal failure but collective forgetting. Forgetting that the house is only a thin shield against the forest. Forgetting that without compassion, our structures collapse back into wilderness. Those without shelter live in the raw exposure most of us keep hidden. They are witnesses, unwilling but undeniable, to the truth that society has turned away from mercy.

The Green Man walks with them. Beyond the walls of ordered life, he shares their seasons, their precarious balance between visibility and invisibility. In the gaps and interstices of the city, his face flickers: dignity in dispossession, endurance carved into survival.

He walks too with the seekers and the estranged, the artists, the hidden, the unassimilated. Many who cannot return from the forest to the rigid grid of order are not broken but marked: creative, intelligent, scarred by hardship, bearing visions that resist domestication. In a culture that fears its own wildness, they are pushed aside, left to wander the borderland between civilisation and wilderness.

Homelessness is a mirror. It shows us neglect made visible, stewardship denied, homes turned to commodities. To call it individual misfortune is to uphold an order that is not social but anti-social. A law of exclusion, where the vulnerable are stripped of care and cast outside the circle of culture.

Against this, the Green Man endures. His leaves whisper that endings feed beginnings, that resilience is woven into the fabric of existence. He teaches that the wheel turns, that loss and renewal are inseparable, that survival is never final defeat. For those on the street, he is not an answer but a companion. A presence that affirms dignity even when stripped bare, endurance even when forgotten.

But he does not linger only there. He is with us all. For we live in an age when nature, long subdued, presses back. Fires, floods, heat rising. The old severity returns, reminding us that dominion is not stewardship, that separation leads not to mastery but to collapse. The lesson carved in stone remains: balance or ruin.

The Green Man’s gaze unsettles because it is not moral but elemental. He does not ask us to be good. He reveals what happens when we forget what we are. His leaves grow through our failures. His eyes follow us into shadow. He waits in the cracks, in the ruins, in the slow turning of the wheel.

He is not comfort, nor threat. He is witness. Reminder. That life is many things, all at once. That it belongs to us, and we to it. That our striving, our building, our dreaming, are branches growing from a root older than memory. And that mercy, hard-won, fragile, necessary, is what allows us not only to survive, but to flourish together.

Archive of Gestures

Archive of Gestures, By Amanda Camenisch

I’m walking.

I walk across dry, hardened earth. The ground beneath my feet is compacted, compressed by the weight and repetition of many footsteps before mine. It does not yield; it remembers. This is not the soft, forgiving soil of untouched terrain, but land that has been walked over, traversed, and perhaps forgotten. Its surface flattened by routine, by passage, by habit. As I walk, I can feel the cadence of my steps reverberate through the bones of my body, echoing into the ground like a quiet drumbeat. I imagine the subtle tremor of my presence moving ahead of me, carried along the subterranean weave of soil and root, alerting small creatures to my approach.

This is Hyde Park. A place once imagined for leisure, now more often a corridor. A space between origins and destinations. I cross it not as its steward but as its stranger. This land does not belong to me, nor I to it. It is managed by the City of London, maintained as civic terrain. Yet some part of me longs for a different relationship, one of intimacy, responsibility, and kinship.

My ancestors were farmers. I was taught early on that no soil is neutral. Land is not inert; it is alive. It requires care, attention, reciprocity. They saw themselves not as owners, but as caretakers. Participants in a sacred contract between heaven and earth, humans and the more-than-human world. Boundaries, in their cosmology, were not assertions of possession but markers of responsibility. To tend the land meant to listen, to observe, to prune what is sick, to harvest only what has ripened, to sow seeds with care and to wait patiently, prayerfully, for the earth to respond. When the spirits of the land were willing, there would be yield. In this practice, the sacred and the practical were not separate but inseparable. Spirituality was not an abstraction; it was a rhythm, a cycle, a task. It made sense because it had purpose and in that purpose, there was meaning.

But a question persists within me: as we walk the earth, tracing the outlines of a landscape shaped by memory and time, what are we tracing in the sky? We are not the only ones in motion. The planets spin, the stars revolve, the galaxy itself spirals. We are part of this vast choreography. In ancient traditions, maps were not simply tools for navigation; they were sacred diagrams, cosmograms, incantations. They encoded not just geography, but metaphysics. They marked the paths not only of humans, but of spirits. It is unclear whether humans follow the tracks of spirits or spirits trace the paths of humans, but their movements most likely intersect. Crossroads, wells, cairns, these were always more than landmarks. They were thresholds, energetic nodes, places where the veil thinned.

What, then, are the equivalents of these sacred nodes within the body? What rivers of energy, what meridians or ley lines, run through us? Where do the footpaths of our ancestors continue within the corridors of our muscles, our instincts, our longings? To what extent are our choices, the paths we take or avoid, shaped by inherited rhythms, ancestral memories, or the silent inscriptions of history moving through our blood?

Rhythm, then, is more than sound. It is inscription. It writes itself across the body. It stores memory in muscle. It reveals the hidden geometries that bind us to the land, to time, to one another.

A map opens up which knows no boundaries.

Tim Ingold distinguishes between mapmaking, a god’s-eye abstraction used to assert ownership, and mapping, which emerges from within a world already alive, entangled, and responsive. Mapping is embodied. It is the act of moving with awareness through space, allowing the rhythms of our bodies and the memory of landscape to merge. Mapping is a form of home-making, not in the architectural sense, but in the sacred sense of locating oneself within a cosmology.

In this view, land is not a resource, but a relationship. Myths and stories that arise from certain rivers, forests, or stones are ontological coordinates. They tell us who we are, where we come from, and how we are to move. Our ancestors understood this land to be sacred not as metaphor, but as truth. They personalised the land out of reverence. Mountains were not inert formations but elders. Lakes were not water bodies but portals. Stones carried stories, and trees bore witness. Every movement one made had to be in alignment with the spirits of nature and the universe. Nothing simply existed outside this sacred order. Every gesture was part of a larger cycle, a cosmological choreography in which human action was participatory. It is within this circling stream that we move, as extensions of ancestral pathways, divine rhythms, and sacred terrain.

To walk the earth is to move one living organism across the living body of another. In this movement, two rhythms emerge: the beat of the heart and the pace of our steps. The heartbeat, primal and sonic, is first perceived within the watery womb. After birth, it becomes internal, less legible, but still present. The walk, however, is a rhythm we externalise. It is paced. It is audible. It is, in many ways, our first act of rhythm-making in the world. Our feet drum rhythms upon the land. In aligning with rhythm, we align with cosmic time, a sonic geometry: invisible yet profoundly structuring, grounding the body in time, and the soul in place. As we walk, we do not merely move across land, we become part of its remembering.

In earlier cultures, journeys were not just practical; they were spiritual. Rhythm, in this context, is a navigation system, both terrestrial and transcendent. Music was played and songs were sung to remember the way. The cadence of footsteps, the lilt of a melody, the tempo of a dance. These were mnemonic devices that encoded direction, destination, and devotion. Walking the earth and journeying through the inner world were entangled experiences.

If rhythm is encoded within us, inherited through blood and bone, then perhaps it offers more than memory. Perhaps it offers orientation. My own body reveals this: though raised in flat lands all my ancestors came from steep mountain areas. I am deeply comfortable in steep terrain. I do not stumble. I climb with ease. I am sure-footed in the mountains as if my body remembers a time, or a people, before me. Movement, then, is not merely learned. It is inherited.

And what I was seeking is suddenly revealed.

What if our bodies carry songs we’ve never sung? What if our gestures are archives, repositories of memory passed down through blood, bone, and breath? I began to wonder if our internal rhythm is not only our own, but the echo of ancestral songs, human and more-than-human, expressing themselves through us, often without our awareness.

This question became the foundation of a long-term project I initiated together with my collaborator Therese Westin. We call it The Archive of Gestures. Over the past four years, we’ve worked with migrants, refugees, and trauma survivors, engaging in a long-term performance project that explores movement as a pathway to memory, healing, and connection.

One foundational practice involves offering spontaneous movements, often emerging from a need for release, comfort, or expression. Repeatedly, we found that these movements were not arbitrary. They reached back, into early childhood, into ancestral practices, into gestures of farming, sewing, caretaking, or cultural dances long forgotten. Some carried the memory of rituals participants had never formally learned. Others surfaced from places of longing, displacement, or generational silence. These were not merely physical expressions. They were archives, living memory encoded in the body, revealing what had been forgotten, avoided, or suppressed.

In these workshops, the body becomes both witness and teacher. It speaks a language older than words, a kinetic language of survival, adaptation, and belonging. The body holds the score, not only of trauma, but of inherited knowledge. It tells us where to move, what to release, and how to remember who we are.

Imagine a world where we are born into blankness, required to learn everything from scratch. It would be unbearable. But we are not blank slates. We are born into rhythms. Into movements shaped by thousands of years. Into bodies that have already learned how to live, move, protect, and care.

The Archive of Gestures became a way to honour this inheritance, but also as a tool for relational empathy. In mirroring and mimicking each other’s gestures, we enter their experience. We listen with our limbs. We reflect not only what we see, but what we feel. In this shared movement, deep connections were forged, often bypassing language altogether.

What emerges are movements that open gateways between now and then, between us and our ancestors, between trauma and transformation. As gestures arise, they bring with them insights, grief, wisdom, and the desire for release. We witness how the body, when allowed to speak, reveals what it longs for: alignment, remembrance, and movement toward flourishing.

These gestures are sacred cartographies. They are maps of resilience. They trace the pathways of those who came before, who survived so that we could move. In reclaiming these movements, we reclaim parts of ourselves. We do not just remember, we become the memory made flesh.

A vehicle for a seed.

Entering these states of kinetic exploration, gestural awareness and rhythmic play, the body quickly finds itself in trance. Movements loop. A gesture repeats again and again. Rhythm emerges not as performance but as mediation. Work becomes dance. A trance unfolds.

I began to notice how working the land mirrors this: repetition, tempo, the hypnotic cadence of care. One reaps or churns, bends and sows, hour after hour, always the same gestures, syncopated with the breath of the earth. You rock a child. You walk for hours. You sing while planting seeds. A rhythm lives here, passed through muscle memory, unspoken but deeply known.

In diasporic contexts, rhythm crosses oceans. A beat played in London can summon the spirits of the ancestors and thus the homeland. The body becomes vessel, acoustic, ritual, mnemonic. It collapses time. In our performance work, we’ve seen this: a single beat transforms a sterile gallery into forest, shrine, field, an altar.

I began to see this work as a circle. Not simply a choreography, but an alchemical loop. We begin in exploration, unraveling what has been buried. We move toward revelation. We birth something. And then we reflect on what was created, what was healed, what now grows.

Many of our participants are descended from farming communities, and so am I. This surfaced again and again, movements of tending, digging, carrying. Gestures of harvest and hope. In working with these kinetic memories, a collective desire emerged: to plant. To return to soil. To work with the elements, earth, air, fire, water, and with the beings who inhabit those realms. Not metaphorically, but alchemically.

There is nothing more alchemical than growing food. To place a seed in earth and transform it into sustenance is a form of spellwork. It is practical magick. To know what to plant, when to water, how to tend, is sacred intelligence. It is not just food that grows. It is us.

The body is the vessel that holds the seed. When we perform it, we remember. When we move, we record. When we plant, we heal.

To position the body as both auditory and metaphysical map is to place it at the center of survival, spirit, and somatic knowledge. Movement becomes the ritual through which the archive is remembered, reactivated, and rewritten.

We are always walking ancient paths, laid by ancestors who sang with their feet, listened with their hips, healed with their hands. The body, then, is not just a vehicle. It is the breath between past and future. It is rhythm made visible. An Archive of belonging.

Energy Made Visible

Energy Made Visible: A Meditation on Musical Dance Performances as a Way of Governance and Healing among the Kel Tamasheq, By Amanda Camenisch

“Music when you posess me, words fail to make you apology.

Everything is so intense in my heart, that your sweet noted irrigate me.

Everything becomes wonders and reasons.

You are peace, rest and serenity.

You are in me, you are everywhere.

Universal chain, my body is your receptacal.

You follow me tirelessly everywhere.

I find you in the hollow and the crest of the waves.

When the wind blows in nature, the murmuring of rocked leaves,

the furrows that zebra the dunes of sand, it is still you.

Thanks to you I know how to listen and understand.

You are respect for difference.

You are love, you are tolerance, tenderness and joy.

You bring people together and unite them.

Music when you hold me by the dance i try to translate you to give you a form.”

Keltoum S. Walet

–––

There are moments in which sound becomes a kind of gravity. An unseen architecture that arranges bodies in motion, gestures in correspondence, time in vibration. To speak of energy made visible is to speak of this invisible ordering: the subtle ways that rhythm gives shape to relation, how movement translates what exceeds language, how performance becomes a form of knowing.

In the histories of nomadic life, energy is not metaphorical. It is the pulse of subsistence and survival, a choreography of adaptation, a lived ethics of attunement. Movement is never only displacement; it is the medium through which knowledge circulates, like wind carrying stories across dunes, like songs rippling through gatherings under a changing sky. The Kel Tamasheq know this: that to move is to remember, to realign the self within a continuum larger than one’s body, to repeat without repetition, to live in correspondence with the invisible.

In such a world, dance is not performance but translation. It translates what cannot be spoken — grief, reverence, resilience — into a visible current. The dancer is not a performer but a vessel through which time passes. In this sense, energy becomes both aesthetic and metaphysical: an expression of vitality, yes, but also of relation, of the constant negotiation between what is felt and what is formed. Every gesture contains an ethics of care, for the community that witnesses, for the ancestors that return through rhythm, for the earth that holds the vibration.

To call this energy “visible” is already a paradox. Visibility in the Western lexicon often implies objecthood, a stable thing to be seen. But the visibility here is not of form, it is of becoming. It flickers, appears and disappears, like breath against the horizon. It cannot be fixed, only encountered. The visibility of energy is relational; it exists only through presence, through participation, through the shared pulse between bodies that listen to one another.

The philosopher Thomas Nail writes of movement as the first reality not as what happens to things, but as what things are. In this sense, performance is not a representation of life, but its continuation by other means. The dance, the song, the drumbeat, these are modes of being in motion, not metaphors for it. They resist the static, the bounded, the possessive. They dissolve the division between self and world, performer and audience, here and elsewhere. What appears as choreography is in fact cosmology.

Across the Sahara, one can still hear the hum of electric guitars, the pulse of tende drums, the ululation of women’s voices rising in praise or critique. In these gatherings, art is not separated from life, nor spirit from governance. A festival is a parliament of energies: a space in which social tensions are released through sound, where wrongs are named and relationships renewed through rhythm. The song is an argument, the dance a resolution, the laughter a law. Through repetition, communities enact their continuity; through improvisation, they affirm their capacity for change.

To dance, then, is to legislate differently, to ground law in affect, to make the communal body the site of articulation. This is not utopian; it is ancient. The Kel Tamasheq understand that beauty and justice are not opposites, but interdependent modes of balance. The one restores the other. The dancer, in their spiralling gestures, does not only entertain but harmonises: mediating between the visible and the invisible, the individual and the collective, the living and the remembered.

There is a humility in this practice, a refusal to claim authorship over movement. Energy, after all, belongs to no one. It merely passes through. In this sense, performance becomes a kind of listening: listening to what the body remembers before the mind explains, listening to the ways land moves through people, to how sound carries emotion into air. To dance is to surrender to that passage, to accept that meaning is transient, that clarity arrives through motion rather than stasis.

This awareness troubles the modernist desire for documentation and preservation. The camera, in this context, cannot “capture” a dance; it can only accompany it. Each frame is already a translation, an echo of something that exceeds its lens. The documentation of movement becomes an ethics of witnessing: an acknowledgment of impermanence rather than an attempt to arrest it. The archive, therefore, must learn to breathe, to shift from a repository of evidence to a living network of relations.

This is what makes the idea of a mobile archive — like a tent that travels — so profound. It embodies the same rhythm as transhumance: the cyclical migration that sustains both life and knowledge. It refuses the binary of centre and periphery, replacing it with circulation, encounter, exchange. Within such a structure, art does not accumulate; it unfolds. Meaning does not solidify; it multiplies. To move is to think otherwise.

In the contemporary world, where borders harden and mobility is often framed as crisis, the wisdom of nomadism offers another measure of belonging. It teaches that stability is not the absence of motion but its rhythm, the ability to remain in relation while moving through change. The body in dance mirrors the planet in orbit: continuous, cyclical, uncontained. The ethics of movement lies not in possession but in participation, not in permanence but in renewal.

The philosopher Édouard Glissant spoke of relation as an oceanic condition, a poetics of interdependence in which each element retains its opacity. Energy, in this sense, is not a universal substance but a shared vibration that holds difference without resolving it. The dance gathers these vibrations, weaving them into temporary constellations of sense. Each movement is a gesture toward connection, an offering to the unseen.

In moments of performance, the boundaries between body, instrument, and environment dissolve. The drumbeat echoes the heartbeat, the voice carries wind, the sand remembers the step. This is the ecology of resonance: a mode of knowing that recognises the interpenetration of all things. Energy made visible is not a spectacle, but a form of attention, an invitation to perceive the invisible correspondences that sustain life.

To speak of energy is also to speak of responsibility. The moment one realises that vitality flows through all beings, ethics ceases to be external. It becomes embodied, a rhythm of reciprocity. To move with awareness is to honour the flow, to resist extraction, to remain in care. The dance becomes a site of repair: not as performance of healing but as its enactment, moment by moment, gesture by gesture.

In this way, art and spirituality converge not as belief systems but as practices of orientation. Both ask: how do we move in the world? How do we listen? How do we give form to the invisible? The answer is never singular. It arises in the in-between. Between languages, between bodies, between histories. Translation, then, is not a technical act but a metaphysical one: to carry meaning across without owning it, to dwell within difference without demanding its resolution.

There is a story that says when the wind crosses the desert, it speaks in many tongues. Each dune becomes a syllable, each grain of sand a memory of movement. To listen is to participate in this conversation, to become porous to its rhythm. The musician, the dancer, the filmmaker, each in their own way, learns to listen differently: to make form from the murmuring, to shape attention into expression.

In this listening, one begins to sense the world as choreography: a ceaseless interplay of forces that exceed comprehension. The role of art, perhaps, is not to make sense of it, but to remain with it, to give shape to wonder without exhausting it. To allow beauty to remain a form of thinking, not a distraction from it.

What is revealed in these movements is a truth about humanity that resists simplification. That we are not defined by what we possess, but by how we move. That meaning does not arise from control, but from relation. That the visible is only ever the threshold of the invisible.

When the dancer steps into the circle, when the music begins, when the air trembles with anticipation. There, for a moment, the world reconfigures itself. The ordinary becomes ceremonial. The human becomes porous to the more-than-human. Energy becomes visible, not as spectacle, but as presence.

And perhaps this is all art ever does: it slows the pulse of experience just enough for us to perceive the invisible work of connection. It reveals the rhythms already there, between us, within us, around us. It teaches us, again and again, that to be alive is to be in motion, that to move is to know, that to know is to listen.

Harmonic Resonance as Practice

Music, Sound and Harmony as a way of attuning to inner resonance.

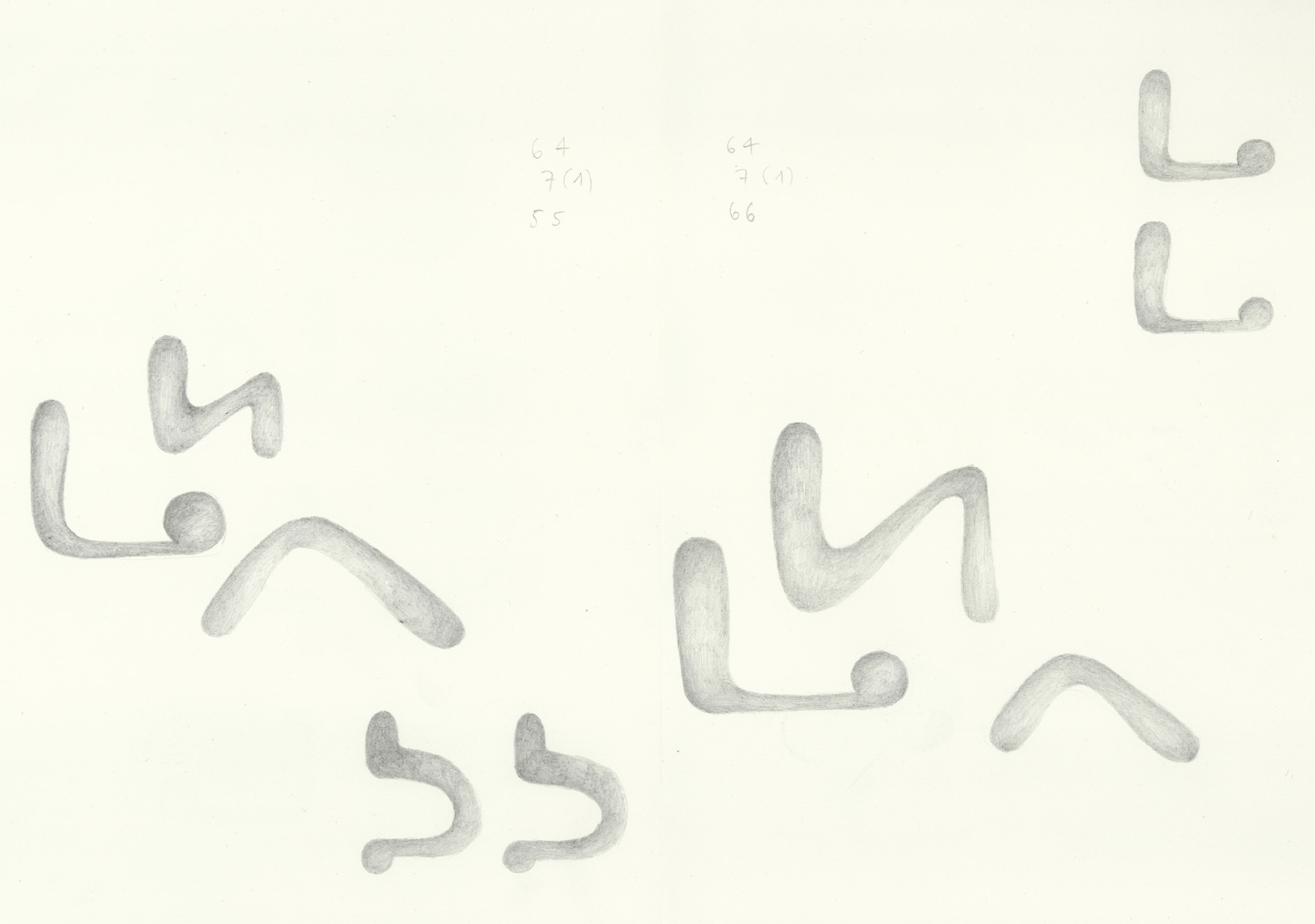

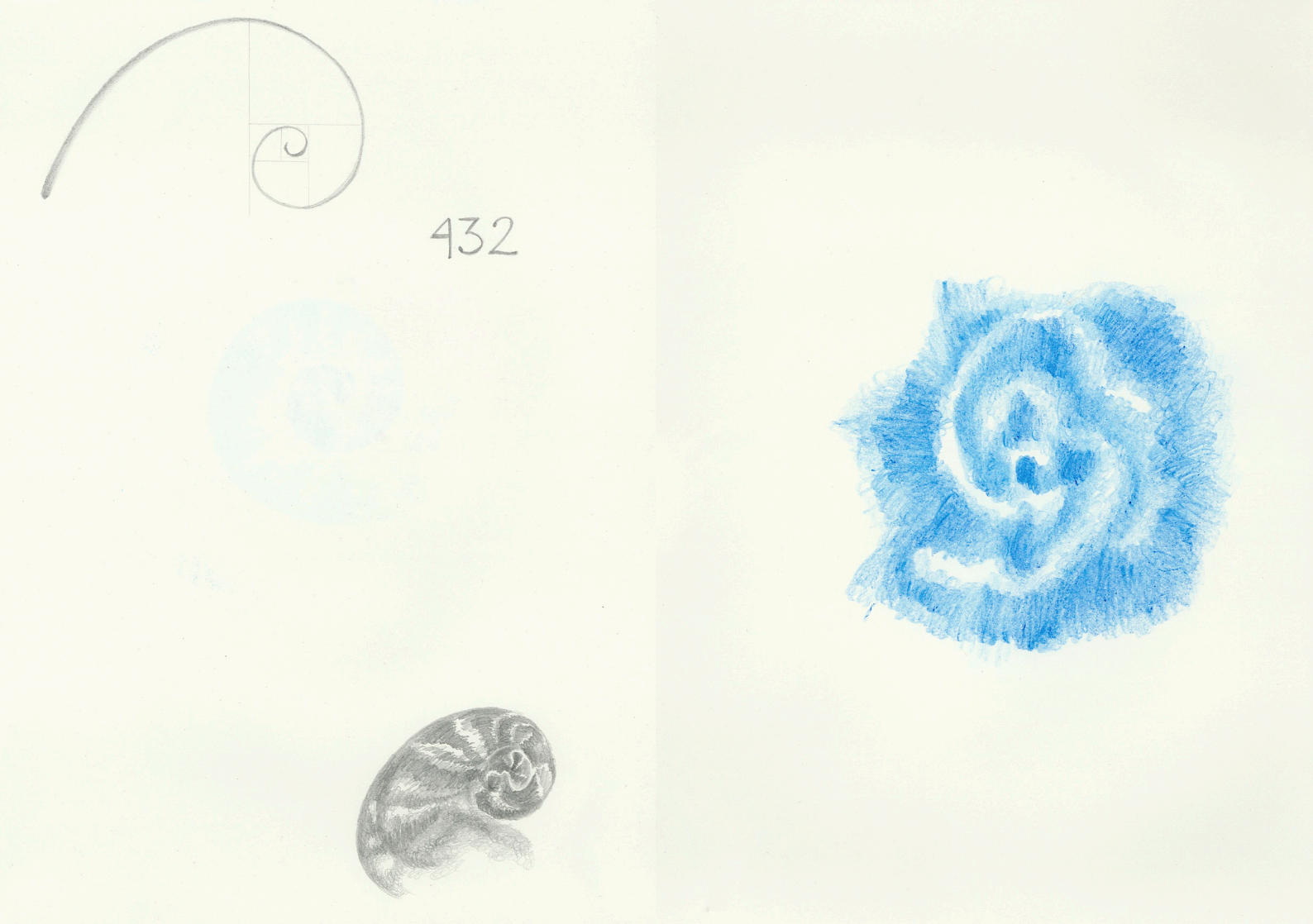

Excerpts from Handmade Books

Selected pages from handmade books created by Amanda Camenisch and Therese Westin for the projects Singing Blankets, Lyra, and Making the Room Sing. These include exercises, visualizations, journaling prompts, and participants’ sonic and somatic drawings.